India’s pursuit of defence self-reliance has always been a high-stakes, uphill climb. Few programs embody both its ambition and its systemic flaws more clearly than the Kaveri engine. Launched in 1986 with the aim of powering the Light Combat Aircraft (LCA) Tejas, the Kaveri was meant to signal the arrival of India as an aerospace power. Nearly four decades later, it has quietly exited the manned fighter stage, repurposed instead for unmanned systems. The end of the Kaveri’s original mission isn’t just a technical story, it’s a hard reckoning with the chronic inefficiencies of India’s defence Public Sector Undertakings (PSUs).

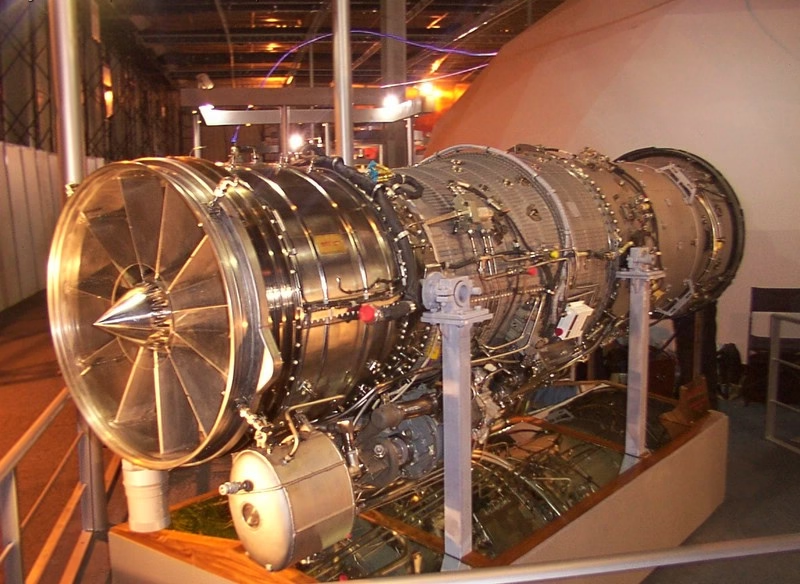

The Kaveri was supposed to be a game-changer: an 81 kN thrust engine built entirely in-house by the DRDO’s Gas Turbine Research Establishment. But it never met thrust or weight requirements, consistently underperforming in tests and tipping the scales 135 kilograms above design. Despite nine prototypes, 3,000 hours of ground testing, and 73 flight hours on a Russian Il-76 testbed, the engine never made it to operational service. By 2004, the Aeronautical Development Agency had moved on to General Electric’s F404-IN20 for the Tejas. That was the quiet death of Kaveri’s fighter ambitions.

Today, what remains is the Kaveri Derivative Engine (KDE), a non-afterburning variant undergoing final flight testing in Russia, expected to power India’s Ghatak stealth Unmanned Combat Aerial Vehicle. It is a pragmatic pivot, but also an admission. The DRDO’s chief, Dr. Samir Kamat, confirmed that Kaveri is no longer in the running for manned platforms. That statement closes a 39-year chapter that cost India over ₹2,000 crore and countless hours of R&D effort. The knowledge gained is real, but so are the opportunity costs.

Kaveri’s failure is not isolated. It reflects a deeper malaise within India’s military-industrial establishment, particularly in its PSUs. Institutions like HAL, BEL, and others have made undeniable contributions: Tejas, Arjun, Akash, and dozens of radar and missile systems were all delivered, albeit slowly. But delays, missed benchmarks, and dependency on imports have remained constants.

Projects are perpetually late. HAL took nearly three decades to move Tejas from concept to limited operational clearance. The Arjun tank was conceived in the 1970s but only entered limited service in the 2010s, with the Army ultimately preferring Russian T-90s. Critical systems, from single-crystal turbine blades to high-altitude test facilities, are still sourced or leased from abroad. India’s metallurgy and aerothermal science remain underdeveloped relative to its aspirations.

These shortcomings have operational consequences. The Indian Air Force’s fighter squadron strength has dipped to 31 from the sanctioned 42. The slow induction of Tejas and the absence of an indigenous engine have forced continued reliance on GE and other foreign suppliers. With the AMCA on the horizon, India still lacks a certified domestic engine powerful enough to meet its needs.

The comparison with ISRO is instructive. India has built and flown cryogenic engines. It has launched Mars and lunar missions. What’s different is not just the science, but the structure: funding consistency, autonomy in project management, and an internal culture that encourages experimentation over paperwork.

That’s where the Kaveri story turns toward reform. The data, expertise, and testing infrastructure built for the Kaveri are not lost. They form a foundation, imperfect but vital, for what must come next. The public discourse around #FundKaveriEngine reflects this urgency. There is now a growing recognition that India needs a second, better-funded push: Kaveri 2.0, possibly in partnership with firms like Safran or Rolls-Royce but built with full local ownership.

For that to work, PSUs must evolve. Bureaucratic inertia, delayed procurement, and leadership silos have to give way to faster decision-making, flexible staffing, and a greater role for private-sector engineering and design. The future lies in hybrid models, public sector infrastructure, private-sector agility. Recent contracts with firms like ideaForge in the UAV space show the way.

The Modi government has shown a willingness to confront these bottlenecks. Schemes like Atmanirbhar Bharat in defence have opened the door for private startups. Indigenous orders for platforms like Tejas Mk1A, Akash NG, and Pinaka systems have been accelerated. The 10% reservation for economically weaker sections has also created a framework for broader talent entry into engineering and aerospace research. This is a start. But scaling these changes will require political will, deep investment in R&D, and risk tolerance from institutional gatekeepers.

The Kaveri engine did not fail for lack of vision. It failed due to neglect at critical moments, both financial and administrative. Its afterlife in UAVs is not defeat, it’s reinvention. But the lessons it leaves behind must not be shelved like its prototypes. A country that aspires to strategic autonomy cannot outsource its engine room forever.

The next war India fights may not wait for imports. The next opportunity to break this cycle may not come again soon. The Kaveri is dead—for the fighter jet. But the resolve to build its successor must live on. Long live the defence PSU, but only if they are reformed, revitalized, and ready to deliver.

Leave a Reply